CAZypedia celebrates the life of Senior Curator Emeritus Harry Gilbert, a true giant in the field, who passed away in September 2025.

CAZypedia needs your help!

We have many unassigned pages in need of Authors and Responsible Curators. See a page that's out-of-date and just needs a touch-up? - You are also welcome to become a CAZypedian. Here's how.

Scientists at all career stages, including students, are welcome to contribute.

Learn more about CAZypedia's misson here and in this article. Totally new to the CAZy classification? Read this first.

Difference between revisions of "Auxiliary Activity Family 5"

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

== General Properties == | == General Properties == | ||

| − | Enzymes from the CAZy family AA5 are mononuclear copper-radical oxidases (CRO) that perform catalysis independently of complex organic cofactors such as FAD or NADP and use oxygen as their electron acceptor ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.- EC 1.1.3.-]).Family AA5 enzymes are classified in two subfamilies: subfamily AA5_1 contains characterized glyoxal oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.2.3.15 EC 1.2.3.15]) <cite>Daou2017</cite> and subfamily AA5_2 contains galactose oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.9 EC 1.1.3.9]) <cite>Whittaker2003</cite>, as well as the more recently discovered raffinose oxidases <cite>Andberg2017,Cleveland2021b</cite>, aliphatic alcohol oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.13 EC 1.1.3.13]) <cite>Yin2015,Oide2019,Cleveland2021b</cite> and aryl alcohol oxidase ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.7 EC 1.1.3.7]) <cite>Mathieu2020;Cleveland2021a</cite>. | + | Enzymes from the CAZy family AA5 are mononuclear copper-radical oxidases (CRO) that perform catalysis independently of complex organic cofactors such as FAD or NADP and use oxygen as their electron acceptor ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.- EC 1.1.3.-]). Family AA5 enzymes are classified in two subfamilies: subfamily AA5_1 contains characterized glyoxal oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.2.3.15 EC 1.2.3.15]) <cite>Daou2017</cite> and subfamily AA5_2 contains galactose oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.9 EC 1.1.3.9]) <cite>Whittaker2003</cite>, as well as the more recently discovered raffinose oxidases <cite>Andberg2017,Cleveland2021b</cite>, aliphatic alcohol oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.13 EC 1.1.3.13]) <cite>Yin2015,Oide2019,Cleveland2021b</cite> and aryl alcohol oxidase ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.7 EC 1.1.3.7]) <cite>Mathieu2020;Cleveland2021a</cite>. |

The most studied enzyme in subfamily AA5_1 is the glyoxal oxidase from ''Phanerochaete chrysosporium'' discovered in 1987 <cite>Kersten1987</cite>. For subfamily AA5_2, the archetypal galactose-6 oxidase from Fusarium graminearum (FgrGalOx) was first reported in 1959 from cultures of ''Polyporus circinatus'' (later renamed ''Fusarium graminearum'' <cite>Ogel1994,Cooper1959</cite>. While this first report already established ''Fgr''GalOx as a metalloenzyme; its copper requirement was later confirmed <cite>Amaral1963</cite>. Until 2015 the characterized enzymes from the AA5_2 subfamily were found to exhibit mainly galactose oxidase activity, but since then novel non-carbohydrate oxidase enzymes were found <cite>Yin2015,Oide2019,Mathieu2020,Cleveland2021a,Cleveland2021b</cite>. | The most studied enzyme in subfamily AA5_1 is the glyoxal oxidase from ''Phanerochaete chrysosporium'' discovered in 1987 <cite>Kersten1987</cite>. For subfamily AA5_2, the archetypal galactose-6 oxidase from Fusarium graminearum (FgrGalOx) was first reported in 1959 from cultures of ''Polyporus circinatus'' (later renamed ''Fusarium graminearum'' <cite>Ogel1994,Cooper1959</cite>. While this first report already established ''Fgr''GalOx as a metalloenzyme; its copper requirement was later confirmed <cite>Amaral1963</cite>. Until 2015 the characterized enzymes from the AA5_2 subfamily were found to exhibit mainly galactose oxidase activity, but since then novel non-carbohydrate oxidase enzymes were found <cite>Yin2015,Oide2019,Mathieu2020,Cleveland2021a,Cleveland2021b</cite>. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

==== AA5_2 ==== | ==== AA5_2 ==== | ||

| − | The founding member of AA5_2 from ''Fusarium graminearum'' is a galactose oxidases (''Fgr''GalOx), which catalyzes the regioselective oxidation of the C6-hydroxyl group on the monosaccharide galactose ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.7 EC 1.3.3.7]) <cite>Avigad1962</cite>. The range of substrates oxidized by ''Fgr''GalOx includes galactose derivatives such as 1-methyl-b-galactopyranoside <cite>Paukner2015</cite>, and galactose-containing oligo-and polysaccharides including: lactose, melibiose, raffinose, galactoxyloglucan, galactomannan and galactoglucomannan <cite>Parikka2015,Parikka2010</cite>. Most other AA5_2s from the ''Fusarium'' family, such as ''F. oxysporum'' <cite>Paukner2014<cite>, ''F. sambucinum'' <cite>Paukner2015<cite>, and ''F. acuminatum'' <cite>Alberton2007</cite> have similar substrate specificities to ''Fgr''GalOx. | + | The founding member of AA5_2 from ''Fusarium graminearum'' is a galactose oxidases (''Fgr''GalOx), which catalyzes the regioselective oxidation of the C6-hydroxyl group on the monosaccharide galactose ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.7 EC 1.3.3.7]) <cite>Avigad1962</cite>. The range of substrates oxidized by ''Fgr''GalOx includes galactose derivatives such as 1-methyl-b-galactopyranoside <cite>Paukner2015</cite>, and galactose-containing oligo-and polysaccharides including: lactose, melibiose, raffinose, galactoxyloglucan, galactomannan and galactoglucomannan <cite>Parikka2015,Parikka2010</cite>. Most other AA5_2s from the ''Fusarium'' family, such as ''F. oxysporum'' <cite>Paukner2014</cite>, ''F. sambucinum'' <cite>Paukner2015</cite>, and ''F. acuminatum'' <cite>Alberton2007</cite> have similar substrate specificities to ''Fgr''GalOx. |

In 2015, two AA5_2 oxidases with distinct substrate profiles were discovered from ''Colletotrichum graminicola'' and ''Colletotrichum gloeosporioides'' (''Cgr''AlcOx and ''Cgl''AlcOx) that were essentially inactive on galactose and galactosides, but efficiently oxidized the primary hydroxyl of diverse aliphatic and aromatic alcohols <cite>Yin2015</cite>. Due to these enzymes exhibiting high specificity towards 1-butanol, benzyl alcohol and cinnamyl alcohol, they were classified as general alcohol oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.13 EC 1.3.3.13]) <cite>Yin2015</cite>. In addition, two alcohol oxidases were characterized from the rice blast pathogen ''Pyricularia oryzae'' (''Por''AlcOx) and from ''C.'' ''higginsianum'' (''Chi''AlcOx) with both enzymes showing prominent activity on n-butanol, ethanol, 1,3-butanediol and glycerol <cite>Oide2019</cite>. Since then, more AA5_2 enzymes from various fungal origins have been characterized as general alcohol oxidases, some being able to efficiently oxidize both carbohydrate and non-carbohydrate substrates (ex.''Afl''AlcOx) <cite>Cleveland2021b</cite>. | In 2015, two AA5_2 oxidases with distinct substrate profiles were discovered from ''Colletotrichum graminicola'' and ''Colletotrichum gloeosporioides'' (''Cgr''AlcOx and ''Cgl''AlcOx) that were essentially inactive on galactose and galactosides, but efficiently oxidized the primary hydroxyl of diverse aliphatic and aromatic alcohols <cite>Yin2015</cite>. Due to these enzymes exhibiting high specificity towards 1-butanol, benzyl alcohol and cinnamyl alcohol, they were classified as general alcohol oxidases ([{{EClink}}1.1.3.13 EC 1.3.3.13]) <cite>Yin2015</cite>. In addition, two alcohol oxidases were characterized from the rice blast pathogen ''Pyricularia oryzae'' (''Por''AlcOx) and from ''C.'' ''higginsianum'' (''Chi''AlcOx) with both enzymes showing prominent activity on n-butanol, ethanol, 1,3-butanediol and glycerol <cite>Oide2019</cite>. Since then, more AA5_2 enzymes from various fungal origins have been characterized as general alcohol oxidases, some being able to efficiently oxidize both carbohydrate and non-carbohydrate substrates (ex.''Afl''AlcOx) <cite>Cleveland2021b</cite>. | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

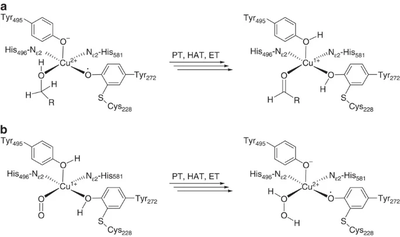

A substantial amount of spectroscopic evidence has supported a ping-pong mechanism for AA5 enzymes <cite>Whittaker2003,Whittaker2005,Baron1994,Humphreys2009,Whittaker1993,Whittaker1996,Whittaker1999,Kersten2014</cite>, including some theoretical and biomimetic models possessing mechanistic similarities <cite>Wang1998,Himo2000</cite>. The reaction progresses through a two-step process: the first half-reaction performs the oxidation of the substrate, while the second half-reaction regenerates the oxidation state of the active-site copper with concurrent reduction of molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide. Each half reaction consists of three steps: proton transfer (PT), hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) and an electron transfer (ET). | A substantial amount of spectroscopic evidence has supported a ping-pong mechanism for AA5 enzymes <cite>Whittaker2003,Whittaker2005,Baron1994,Humphreys2009,Whittaker1993,Whittaker1996,Whittaker1999,Kersten2014</cite>, including some theoretical and biomimetic models possessing mechanistic similarities <cite>Wang1998,Himo2000</cite>. The reaction progresses through a two-step process: the first half-reaction performs the oxidation of the substrate, while the second half-reaction regenerates the oxidation state of the active-site copper with concurrent reduction of molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide. Each half reaction consists of three steps: proton transfer (PT), hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) and an electron transfer (ET). | ||

| − | Other work, focused on optimizing the industrial potential of AA5 enzymes, has shown that AA5_2 enzymes have increased activity with the addition of peroxidases (horse-radish peroxidase and catalase) and small molecule activators (potassium ferricyanide and magnesium (III) acetate)<cite>Cleveland1975,Hamilton1978,Pedersen2015,Forget2020,Johnson2021</cite>. | + | Other work, focused on optimizing the industrial potential of AA5 enzymes, has shown that AA5_2 enzymes have increased activity with the addition of peroxidases (horse-radish peroxidase and catalase) and small molecule activators (potassium ferricyanide and magnesium (III) acetate) <cite>Cleveland1975,Hamilton1978,Pedersen2015,Forget2020,Johnson2021</cite>. |

== Catalytic Residues == | == Catalytic Residues == | ||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

The unique feature of the AA5 is the covalently linked equatorial tyrosine with an adjacent cysteine by a thioether bond (Tyr 272 and Cys 228 in the archetypal ''Fgr''GalOx) <cite>Ito1991,Ito1994</cite>. The thioether linkage forms spontaneously in the presence of copper and has been shown to stabilize the radical though delocalization that forms on the equatorial tyrosine during catalysis <cite>Rogers2008</cite>. | The unique feature of the AA5 is the covalently linked equatorial tyrosine with an adjacent cysteine by a thioether bond (Tyr 272 and Cys 228 in the archetypal ''Fgr''GalOx) <cite>Ito1991,Ito1994</cite>. The thioether linkage forms spontaneously in the presence of copper and has been shown to stabilize the radical though delocalization that forms on the equatorial tyrosine during catalysis <cite>Rogers2008</cite>. | ||

| − | Another important feature of AA5 enzymes is a secondary shell amino acid that is located on top of the tyrosine-cysteine cofactor. It has been speculated to be critical in determining the substrate specificity, radial stability and redox activity by hydrogen bonding, delocalization and/or by protecting the thioether bond from solvent <cite>Whittaker2003,Rogers2007,Kersten2014, Daou2017</cite>. This residue in AA5_1, based on sequence alignments, has been conserved as a histidine <cite>Kersten2014</cite>, while characterized AA5_2s enzymes have an aromatic residue at this position: a tryptophan in galactose oxidases (W290 in | + | Another important feature of AA5 enzymes is a secondary shell amino acid that is located on top of the tyrosine-cysteine cofactor. It has been speculated to be critical in determining the substrate specificity, radial stability and redox activity by hydrogen bonding, delocalization and/or by protecting the thioether bond from solvent <cite>Whittaker2003,Rogers2007,Kersten2014, Daou2017</cite>. This residue in AA5_1, based on sequence alignments, has been conserved as a histidine <cite>Kersten2014</cite>, while characterized AA5_2s enzymes have an aromatic residue at this position: a tryptophan in galactose oxidases (W290 in ''Fgr''GalOx) <cite>Rogers2007,Cleveland2021b</cite>, a phenylalanine in the ''Colletotrichum'' aliphatic alcohol oxidases <cite>Yin2015</cite>, and a tyrosine in the raffinose oxidases <cite>Andberg2017,Cleveland2021b</cite> and aryl alcohol oxidase from ''Colletotrichum graminicola'' <cite>Andberg2017,Mathieu2020</cite>. Furthermore, an AA5 enzyme from ''Streptomyces lividans'' with activity on glycolaldehyde possesses a tryptophan as the stacking secondary shell residue whose indole ring is oriented differently compared to ''Fgr''GalOx <cite>Chaplin2015,Chaplin2017</cite>. |

== Three-dimensional Structures == | == Three-dimensional Structures == | ||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

<biblio> | <biblio> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

#Andberg2017 pmid=28778886 | #Andberg2017 pmid=28778886 | ||

| Line 97: | Line 93: | ||

#Oide2019 pmid=30885320 | #Oide2019 pmid=30885320 | ||

| − | #Mathieu2020 Mathieu, Y., Offen, W. A., Forget, S. M., Ciano, L., Viborg, A. H., Blagova, E., Henrissat, B., Walton, P.H, Davies, G.J, and Brumer, H. (2020). Discovery of a fungal copper radical oxidase with high catalytic efficiency toward 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and benzyl alcohols for bioprocessing. ACS Catalysis, 10 | + | #Mathieu2020 Mathieu, Y., Offen, W. A., Forget, S. M., Ciano, L., Viborg, A. H., Blagova, E., Henrissat, B., Walton, P.H, Davies, G.J, and Brumer, H. (2020). Discovery of a fungal copper radical oxidase with high catalytic efficiency toward 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and benzyl alcohols for bioprocessing. ACS Catalysis, '''10''', 3042-3058. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acscatal.9b04727 |

#Kersten1987 pmid=3553159 | #Kersten1987 pmid=3553159 | ||

| − | #Ogel1994 Ögel, Z. B.; Brayford, D.; McPherson, M. J., (1994). Cellulose-triggered sporulation in the galactose oxidase-producing fungus Cladobotryum (Dactylium) dendroides NRRL 2903 and its re-identification as a species of Fusarium. Mycol. Res., 98 | + | #Ogel1994 Ögel, Z. B.; Brayford, D.; McPherson, M. J., (1994). Cellulose-triggered sporulation in the galactose oxidase-producing fungus Cladobotryum (Dactylium) dendroides NRRL 2903 and its re-identification as a species of Fusarium. Mycol. Res., '''98''', 474-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pep.2014.12.010 |

#Cooper1959 pmid=13641238 | #Cooper1959 pmid=13641238 | ||

#Amaral1963 pmid=14012475 | #Amaral1963 pmid=14012475 | ||

| Line 124: | Line 120: | ||

#Wright2001 pmid=11551381 | #Wright2001 pmid=11551381 | ||

| − | #Itoh2000 Itoh, S.; Taki, M.; Fukuzumi, S., (2000). Active site models for galactose oxidase and related enzymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 198 | + | #Itoh2000 Itoh, S.; Taki, M.; Fukuzumi, S., (2000). Active site models for galactose oxidase and related enzymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. '''198''', 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00209-X |

| − | #Jazdzewski2000 Jazdzewski, B. A.; Tolman, W. B., (2000). Understanding the copper–phenoxyl radical array in galactose oxidase: contributions from synthetic modeling studies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 200-202, 633-685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00342-8 | + | #Jazdzewski2000 Jazdzewski, B. A.; Tolman, W. B., (2000). Understanding the copper–phenoxyl radical array in galactose oxidase: contributions from synthetic modeling studies. Coord. Chem. Rev. '''200-202''', 633-685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00342-8 |

#Whittaker2003 pmid=12797833 | #Whittaker2003 pmid=12797833 | ||

| Line 138: | Line 134: | ||

#Baron1994 pmid=7929198 | #Baron1994 pmid=7929198 | ||

| − | #Saysell1997 Saysell, C. G.; Barna, T.; Borman, C. D.; Baron, A. J.; McPherson, M. J.; Sykes, A. G., P(1997). Properties of the Trp290His variant of Fusarium NRRL 2903 galactose oxidase: interactions of the GOasesemi state with different buffers, its redox activity and ability to bind azide. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2 | + | #Saysell1997 Saysell, C. G.; Barna, T.; Borman, C. D.; Baron, A. J.; McPherson, M. J.; Sykes, A. G., P(1997). Properties of the Trp290His variant of Fusarium NRRL 2903 galactose oxidase: interactions of the GOasesemi state with different buffers, its redox activity and ability to bind azide. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. '''2''', 702-709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007750050186 |

| − | #Rogers1998 Rogers, M. S.; Knowles, P. F.; Baron, A. J.; McPherson, M. J.; Dooley, D. M., (1998). Characterization of the active site of galactose oxidase and its active site mutational variants Y495F/H/K and W290H by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 275-276, 175-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-1693(97)06142-2 | + | #Rogers1998 Rogers, M. S.; Knowles, P. F.; Baron, A. J.; McPherson, M. J.; Dooley, D. M., (1998). Characterization of the active site of galactose oxidase and its active site mutational variants Y495F/H/K and W290H by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Inorg. Chim. Acta. '''275-276''', 175-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-1693(97)06142-2 |

#Whittaker1999 pmid=10593910 | #Whittaker1999 pmid=10593910 | ||

| Line 150: | Line 146: | ||

#Wang1998 pmid=9438841 | #Wang1998 pmid=9438841 | ||

| − | #Himo2000 Himo, F.; Eriksson, L. A.; Maseras, F.; Siegbahn, P. E. M., (2000). Catalytic Mechanism of Galactose Oxidase: A Theoretical Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 | + | #Himo2000 Himo, F.; Eriksson, L. A.; Maseras, F.; Siegbahn, P. E. M., (2000). Catalytic Mechanism of Galactose Oxidase: A Theoretical Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. '''122''', 8031-8036. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja994527r |

#Cleveland1975 pmid=164209 | #Cleveland1975 pmid=164209 | ||

| Line 156: | Line 152: | ||

#Hamilton1978 pmid=183480 | #Hamilton1978 pmid=183480 | ||

| − | #Pedersen2015 Toftgaard Pedersen, A.; Birmingham, W. R.; Rehn, G.; Charnock, S. J.; Turner, N. J.; Woodley, J. M., (2015) Process Requirements of Galactose Oxidase Catalyzed Oxidation of Alcohols. Org. Process Res. Dev. 19 | + | #Pedersen2015 Toftgaard Pedersen, A.; Birmingham, W. R.; Rehn, G.; Charnock, S. J.; Turner, N. J.; Woodley, J. M., (2015) Process Requirements of Galactose Oxidase Catalyzed Oxidation of Alcohols. Org. Process Res. Dev. '''19''', 1580-1589. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00278 |

#Forget2020 pmid=32108208 | #Forget2020 pmid=32108208 | ||

| Line 165: | Line 161: | ||

#Chaplin2017 pmid=28093470 | #Chaplin2017 pmid=28093470 | ||

| + | #Sola2019 pmid=30852555 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | #Rosatella2011 Rosatella AA, Simeonov SP, Frade RFM, Afonso CAM. (2011) 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) as a building block platform: Biological properties, synthesis and synthetic applications. Green Chem. '''13''', 754-93. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0GC00401D | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Sousa201 Sousa AF, Vilela C, Fonseca AC, Matos M, Freire CSR, Gruter G-JM, Coelho JFJ, Silvestre AJD. (2015) Biobased polyesters and other polymers from 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: a tribute to furan excellency. Polym Chem. '''6''', 5961-83. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5PY00686D | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Yalpani1982 Yalpani, M.; Hall, L. D., (1982) Some chemical and analytical aspects of polysaccharide modifications. II. A high-yielding, specific method for the chemical derivatization of galactose-containing polysaccharides: Oxidation with galactose oxidase followed by reductive amination. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Chem. Ed. '''20''', 3399-3420. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1982.170201213 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Kelleher1986 pmid=3791303 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Schoevaart2004 Schoevaart, R.; Kieboom, T., (2004) Application of Galactose Oxidase in Chemoenzymatic One-Pot Cascade Reactions Without Intermediate Recovery Steps. Top. Catal. '''27''', 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TOCA.0000013536.27551.13 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Leppanen2014 pmid=24188837 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Xu2012 pmid=22422625 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Parikka2012 pmid=22724576 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Mikkonen2014 Mikkonen, K. S.; Parikka, K.; Suuronen, J.-P.; Ghafar, A.; Serimaa, R.; Tenkanen, M., (2014) Enzymatic oxidation as a potential new route to produce polysaccharide aerogels. RSC Advances. '''4''', 11884-11892. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3RA47440B | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Derikvand2016 pmid=26892369 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Alberton2007 pmid=17518413 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Parikka2010 pmid=20000571 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Parikka2015 Parikka, K.; Master, E.; Tenkanen, M., (2015) Oxidation with galactose oxidase: Multifunctional enzymatic catalysis. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. '''120''', 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.06.006 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Ribeaucourt2021 pmid=34147589 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Daou2016 pmid=27260365 | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Leuthner2004 pmid=15578222 | ||

| + | #Kersten1990 pmid=11607073 | ||

#Rogers2008 pmid=18771294 | #Rogers2008 pmid=18771294 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</biblio> | </biblio> | ||

[[Category:Auxiliary Activity Families|AA005]] | [[Category:Auxiliary Activity Families|AA005]] | ||

Revision as of 16:08, 14 September 2021

This page is currently under construction. This means that the Responsible Curator has deemed that the page's content is not quite up to CAZypedia's standards for full public consumption. All information should be considered to be under revision and may be subject to major changes.

- Author: ^^^Maria Cleveland^^^ and ^^^Yann Mathieu^^^

- Responsible Curator: ^^^Harry Brumer^^^

| Auxiliary Activity Family AA5 | |

| Fold | Seven-bladed β-propeller |

| Mechanism | Copper Radical Oxidase |

| Active site residues | known |

| CAZy DB link | |

| https://www.cazy.org/AA5.html | |

General Properties

Enzymes from the CAZy family AA5 are mononuclear copper-radical oxidases (CRO) that perform catalysis independently of complex organic cofactors such as FAD or NADP and use oxygen as their electron acceptor (EC 1.1.3.-). Family AA5 enzymes are classified in two subfamilies: subfamily AA5_1 contains characterized glyoxal oxidases (EC 1.2.3.15) [1] and subfamily AA5_2 contains galactose oxidases (EC 1.1.3.9) [2], as well as the more recently discovered raffinose oxidases [3, 4], aliphatic alcohol oxidases (EC 1.1.3.13) [4, 5, 6] and aryl alcohol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.7) [7, 8].

The most studied enzyme in subfamily AA5_1 is the glyoxal oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium discovered in 1987 [9]. For subfamily AA5_2, the archetypal galactose-6 oxidase from Fusarium graminearum (FgrGalOx) was first reported in 1959 from cultures of Polyporus circinatus (later renamed Fusarium graminearum [10, 11]. While this first report already established FgrGalOx as a metalloenzyme; its copper requirement was later confirmed [12]. Until 2015 the characterized enzymes from the AA5_2 subfamily were found to exhibit mainly galactose oxidase activity, but since then novel non-carbohydrate oxidase enzymes were found [4, 5, 6, 7, 8].

An AA5 enzyme from Arabidopsis thaliana, whose sequence does not fall within the two known subfamilies, has been identified as a putative galactose oxidase, RUBY, and has been demonstrated to promote the cell-to-cell adhesion in the seed coat epidermis of Arabidopsis [13]. Furthermore, an AA5 enzyme (GlxA) has been shown to have activity on glycolaldehyde and the deletion mutant of GlxA from Streptomyces lividans showed loss of glycan accumulation at hyphal tips [14].

Substrate Specificities

An important distinction between the AA5_1 and AA5_2 subfamilies, is that while AA5_1 enzyme catalyze the two-electron oxidation of simple aldehydes and hydroxycarbonyl [15], the AA5_2 members accept alcohol containing substrates and oxidatively form the corresponding aldehyde or acid [16, 17].

AA5_1

The AA5_1 enzymes have been characterized as glyoxal oxidases (EC 1.2.3.15) and show activity on simple aldehydes, α-hydroxycarbonyl, and α-dicarbonyl compounds, with the highest activity observe don glyoxal, methyl glyoxal and glycolaldehyde [9, 15, 18, 19, 20]. Most characterized AA5_1 enzymes show the highest activity on methyl glyoxal [18, 20, 21], however, two glyoxal oxidases form Pycnoporus cinnabarinus demonstrate the highest catalytic efficiency on glyoxylic acid as the substrate [22].

AA5_2

The founding member of AA5_2 from Fusarium graminearum is a galactose oxidases (FgrGalOx), which catalyzes the regioselective oxidation of the C6-hydroxyl group on the monosaccharide galactose (EC 1.3.3.7) [23]. The range of substrates oxidized by FgrGalOx includes galactose derivatives such as 1-methyl-b-galactopyranoside [24], and galactose-containing oligo-and polysaccharides including: lactose, melibiose, raffinose, galactoxyloglucan, galactomannan and galactoglucomannan [17, 25]. Most other AA5_2s from the Fusarium family, such as F. oxysporum [26], F. sambucinum [24], and F. acuminatum [27] have similar substrate specificities to FgrGalOx.

In 2015, two AA5_2 oxidases with distinct substrate profiles were discovered from Colletotrichum graminicola and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (CgrAlcOx and CglAlcOx) that were essentially inactive on galactose and galactosides, but efficiently oxidized the primary hydroxyl of diverse aliphatic and aromatic alcohols [5]. Due to these enzymes exhibiting high specificity towards 1-butanol, benzyl alcohol and cinnamyl alcohol, they were classified as general alcohol oxidases (EC 1.3.3.13) [5]. In addition, two alcohol oxidases were characterized from the rice blast pathogen Pyricularia oryzae (PorAlcOx) and from C. higginsianum (ChiAlcOx) with both enzymes showing prominent activity on n-butanol, ethanol, 1,3-butanediol and glycerol [6]. Since then, more AA5_2 enzymes from various fungal origins have been characterized as general alcohol oxidases, some being able to efficiently oxidize both carbohydrate and non-carbohydrate substrates (ex.AflAlcOx) [4].

Furthermore, another AA5_2 member from C. graminicola has been characterized as an aryl-alcohol oxidase (CgrAAO) due to its high specific activity towards substituted benzyl alcohols and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) (EC 1.1.3.7 and EC 1.1.3.47) [7]. In addition, two AA5_2 homologs from Fusarium species have been classified also as aryl alcohols oxidases (FgrAAO and FoxAAO) [8] and other AA5_2 members have been shown to have prominent activity on HMF with enzymes being able to fully oxidize the furan substrate to FDCA (GciAlcOx) [4].

The last distinct group of AA5_2 enzymes based on substrate specificity are the raffinose-specific oxidases (EC 1.3.3.-). These enzymes show only negligible activity on galactose, were not active towards aliphatic alcohols, however, they showed the highest activity for the tri-saccharide raffinose, the diol glycerol, and the glycolaldehyde dimer [3, 4].

Hence, the AA5_2 family contains a diverse set of enzymes with galactose oxidases, raffinose oxidases, general alcohol oxidases (carbohydrate and non-carbohydrate) and aryl alcohol oxidases. The ability of CROs to oxidize galactose-containing sugars can be utilized for the production of biomaterials from biomass sources [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35] while the ability to oxidize aromatic alcohols to the corresponding aldehydes can be utilized in a variety of applications within the food and fragrance industry [36]. Similarly, the ability of CROs to convert HMF into the bi-functional polymer precursors DFF and FDCA, which is important in the context of bio-polymer manufacturing [37, 38].

Kinetics and Mechanism

AA5 enzymes oxidize their substrate with concurrent reduction of oxygen to hydrogen peroxide in a two-electron process mediated through a free-radical-coupled copper complex mediated through the presence of a redox active Tyr-Cys cofactor. In AA5_2 the Tyr-Cys cofactor exhibits an unusually low reduction potential (+275 mV) [39, 40, 41] compared to unmodified tyrosine in solution (> +800 mV) or in other enzymatic systems [42]. Several factors could contribute to this phenomenon by increasing the stability of the protein free radical including π-stacking with aromatic residues and the electron donating effect of the thioether linkage [2, 43, 44]. In contrast, AA5_1 have reduction potential of around +640 mV [18] which could explain the different oxidizing power of the two subfamilies [15, 41]. One reason for the higher reduction potential of glyoxal oxidases could be subtitution of the secondary shell amino acid Trp in AA5_2 with a His in AA5_1 [15, 41]. In the archetypal AA5_2 member, FgrGalOx, the Trp290His substitution increased the redox potential of the resulting enzyme from +400 mV to +730 mV [45]; however, it also decreased the catalytic efficiency by 1000-fold [46] and perturbed the stability of the [Cu2+ Tyr·] metallo-radical complex at neutral pH [47]. CgrAlcOx and CgrAAO have been speculated to have a lower redox potential than FgrGalOx due to the secondary amino acid substitution (Phe in CgrAlcOx and Tyr in CgrAAO) [5, 7].

A substantial amount of spectroscopic evidence has supported a ping-pong mechanism for AA5 enzymes [2, 15, 18, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51], including some theoretical and biomimetic models possessing mechanistic similarities [52, 53]. The reaction progresses through a two-step process: the first half-reaction performs the oxidation of the substrate, while the second half-reaction regenerates the oxidation state of the active-site copper with concurrent reduction of molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide. Each half reaction consists of three steps: proton transfer (PT), hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) and an electron transfer (ET).

Other work, focused on optimizing the industrial potential of AA5 enzymes, has shown that AA5_2 enzymes have increased activity with the addition of peroxidases (horse-radish peroxidase and catalase) and small molecule activators (potassium ferricyanide and magnesium (III) acetate) [54, 55, 56, 57, 58].

Catalytic Residues

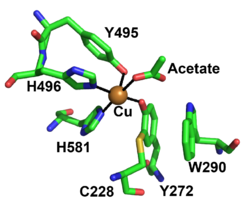

The redox-active center of AA5 oxidases comprises a copper ion that is stabilized by two tyrosines and two histidines (in FgrGalOx, these are Tyr272, Tyr495, His496, His581), resulting in a distorted square pyramidal geometry [2, 18, 48, 51]. Based on the copper coordination environment, AA5 proteins are type 2 “non-blue” copper category due to the nitrogen and oxygen ligands [59]. The unique feature of the AA5 is the covalently linked equatorial tyrosine with an adjacent cysteine by a thioether bond (Tyr 272 and Cys 228 in the archetypal FgrGalOx) [59, 60]. The thioether linkage forms spontaneously in the presence of copper and has been shown to stabilize the radical though delocalization that forms on the equatorial tyrosine during catalysis [61].

Another important feature of AA5 enzymes is a secondary shell amino acid that is located on top of the tyrosine-cysteine cofactor. It has been speculated to be critical in determining the substrate specificity, radial stability and redox activity by hydrogen bonding, delocalization and/or by protecting the thioether bond from solvent [1, 2, 15, 44]. This residue in AA5_1, based on sequence alignments, has been conserved as a histidine [15], while characterized AA5_2s enzymes have an aromatic residue at this position: a tryptophan in galactose oxidases (W290 in FgrGalOx) [4, 44], a phenylalanine in the Colletotrichum aliphatic alcohol oxidases [5], and a tyrosine in the raffinose oxidases [3, 4] and aryl alcohol oxidase from Colletotrichum graminicola [3, 7]. Furthermore, an AA5 enzyme from Streptomyces lividans with activity on glycolaldehyde possesses a tryptophan as the stacking secondary shell residue whose indole ring is oriented differently compared to FgrGalOx [14, 62].

Three-dimensional Structures

AA5 share a seven-bladed β-propeller fold [5, 7, 59] as the catalytic domain containing the active site. The archetypal FgrGalOx contains three domains: domain 1 has a “β sandwich” structure identified as a carbohydrate binding module (CBM32) with affinity for galactose, domain 2 is the catalytic domain and domain 3 is the smallest, which forms a hydrogen bonding network to stabilize domain 2 [59]. Other characterized AA5_2 enzymes from Fusarium species contain CBM32 [4, 24, 26, 63], even though some do not display canonical galactose oxidase activity (ex. FgrAAO and FoxAAO) [4, 8]. In contrast, CgrAlcOx, CglAlcOx and ChiAlcOx do not poses any CBM [5, 6], while CgrAAO and CgrRafOx have a PAN domain present instead [3, 7]. PorAlcOx contained a WSC domain that was able to bind xylans and fungal chitin/β-1,3-glucan, implicating the domains involvement in enzyme anchoring on the plant surface [6]. In addition, the fusion of a galactose oxidase with a CBM29 has shown an increase in catalytic efficiency of the construct on galactose-containing hemicelluloses compared to WT [64].

Family Firsts

- First stereochemistry determination

- Content is to be added here.

- First catalytic nucleophile identification

- Content is to be added here.

- First general acid/base residue identification

- Content is to be added here.

- First 3-D structure

- Content is to be added here.

References

- Daou M and Faulds CB. (2017). Glyoxal oxidases: their nature and properties. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;33(5):87. DOI:10.1007/s11274-017-2254-1 |

- Whittaker JW (2003). Free radical catalysis by galactose oxidase. Chem Rev. 2003;103(6):2347-63. DOI:10.1021/cr020425z |

- Andberg M, Mollerup F, Parikka K, Koutaniemi S, Boer H, Juvonen M, Master E, Tenkanen M, and Kruus K. (2017). A Novel Colletotrichum graminicola Raffinose Oxidase in the AA5 Family. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(20). DOI:10.1128/AEM.01383-17 |

-

pmid=

- Yin DT, Urresti S, Lafond M, Johnston EM, Derikvand F, Ciano L, Berrin JG, Henrissat B, Walton PH, Davies GJ, and Brumer H. (2015). Structure-function characterization reveals new catalytic diversity in the galactose oxidase and glyoxal oxidase family. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10197. DOI:10.1038/ncomms10197 |

- Oide S, Tanaka Y, Watanabe A, and Inui M. (2019). Carbohydrate-binding property of a cell wall integrity and stress response component (WSC) domain of an alcohol oxidase from the rice blast pathogen Pyricularia oryzae. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2019;125:13-20. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.02.009 |

-

Mathieu, Y., Offen, W. A., Forget, S. M., Ciano, L., Viborg, A. H., Blagova, E., Henrissat, B., Walton, P.H, Davies, G.J, and Brumer, H. (2020). Discovery of a fungal copper radical oxidase with high catalytic efficiency toward 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and benzyl alcohols for bioprocessing. ACS Catalysis, 10, 3042-3058. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acscatal.9b04727

- Cleveland M, Lafond M, Xia FR, Chung R, Mulyk P, Hein JE, and Brumer H. (2021). Two Fusarium copper radical oxidases with high activity on aryl alcohols. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2021;14(1):138. DOI:10.1186/s13068-021-01984-0 |

- Kersten PJ and Kirk TK. (1987). Involvement of a new enzyme, glyoxal oxidase, in extracellular H2O2 production by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Bacteriol. 1987;169(5):2195-201. DOI:10.1128/jb.169.5.2195-2201.1987 |

-

Ögel, Z. B.; Brayford, D.; McPherson, M. J., (1994). Cellulose-triggered sporulation in the galactose oxidase-producing fungus Cladobotryum (Dactylium) dendroides NRRL 2903 and its re-identification as a species of Fusarium. Mycol. Res., 98, 474-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pep.2014.12.010

- COOPER JA, SMITH W, BACILA M, and MEDINA H. (1959). Galactose oxidase from Polyporus circinatus, Fr. J Biol Chem. 1959;234(3):445-8. | Google Books | Open Library

- AMARAL D, BERNSTEIN L, MORSE D, and HORECKER BL. (1963). Galactose oxidase of Polyporus circinatus: a copper enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:2281-4. | Google Books | Open Library

- Šola K, Gilchrist EJ, Ropartz D, Wang L, Feussner I, Mansfield SD, Ralet MC, and Haughn GW. (2019). RUBY, a Putative Galactose Oxidase, Influences Pectin Properties and Promotes Cell-To-Cell Adhesion in the Seed Coat Epidermis of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2019;31(4):809-831. DOI:10.1105/tpc.18.00954 |

- Chaplin AK, Petrus ML, Mangiameli G, Hough MA, Svistunenko DA, Nicholls P, Claessen D, Vijgenboom E, and Worrall JA. (2015). GlxA is a new structural member of the radical copper oxidase family and is required for glycan deposition at hyphal tips and morphogenesis of Streptomyces lividans. Biochem J. 2015;469(3):433-44. DOI:10.1042/BJ20150190 |

- Kersten P and Cullen D. (2014). Copper radical oxidases and related extracellular oxidoreductases of wood-decay Agaricomycetes. Fungal Genet Biol. 2014;72:124-130. DOI:10.1016/j.fgb.2014.05.011 |

-

Parikka, K.; Master, E.; Tenkanen, M., (2015) Oxidation with galactose oxidase: Multifunctional enzymatic catalysis. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 120, 47-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.06.006

- Whittaker MM, Kersten PJ, Nakamura N, Sanders-Loehr J, Schweizer ES, and Whittaker JW. (1996). Glyoxal oxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium is a new radical-copper oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(2):681-7. DOI:10.1074/jbc.271.2.681 |

- Leuthner B, Aichinger C, Oehmen E, Koopmann E, Müller O, Müller P, Kahmann R, Bölker M, and Schreier PH. (2005). A H2O2-producing glyoxal oxidase is required for filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;272(6):639-50. DOI:10.1007/s00438-004-1085-6 |

- Kersten PJ (1990). Glyoxal oxidase of Phanerochaete chrysosporium: its characterization and activation by lignin peroxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(8):2936-40. DOI:10.1073/pnas.87.8.2936 |

- Daou M, Piumi F, Cullen D, Record E, and Faulds CB. (2016). Heterologous Production and Characterization of Two Glyoxal Oxidases from Pycnoporus cinnabarinus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(16):4867-75. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00304-16 |

- Paukner R, Staudigl P, Choosri W, Haltrich D, and Leitner C. (2015). Expression, purification, and characterization of galactose oxidase of Fusarium sambucinum in E. coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2015;108:73-79. DOI:10.1016/j.pep.2014.12.010 |

- Parikka K, Leppänen AS, Pitkänen L, Reunanen M, Willför S, and Tenkanen M. (2010). Oxidation of polysaccharides by galactose oxidase. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58(1):262-71. DOI:10.1021/jf902930t |

- Paukner R, Staudigl P, Choosri W, Sygmund C, Halada P, Haltrich D, and Leitner C. (2014). Galactose oxidase from Fusarium oxysporum--expression in E. coli and P. pastoris and biochemical characterization. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100116. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0100116 |

- Alberton D, Silva de Oliveira L, Peralta RM, and Barbosa-Tessmann IP. (2007). Production, purification, and characterization of a novel galactose oxidase from Fusarium acuminatum. J Basic Microbiol. 2007;47(3):203-12. DOI:10.1002/jobm.200610290 |

-

Yalpani, M.; Hall, L. D., (1982) Some chemical and analytical aspects of polysaccharide modifications. II. A high-yielding, specific method for the chemical derivatization of galactose-containing polysaccharides: Oxidation with galactose oxidase followed by reductive amination. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Chem. Ed. 20, 3399-3420. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.1982.170201213

- Kelleher FM and Bhavanandan VP. (1986). Preparation and characterization of beta-D-fructofuranosyl O-(alpha-D-galactopyranosyl uronic acid)-(1----6)-O-alpha-D-glucopyranoside and O-(alpha-D-galactopyranosyl uronic acid)-(1----6)-D-glucose. Carbohydr Res. 1986;155:89-97. DOI:10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90135-6 |

-

Schoevaart, R.; Kieboom, T., (2004) Application of Galactose Oxidase in Chemoenzymatic One-Pot Cascade Reactions Without Intermediate Recovery Steps. Top. Catal. 27, 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TOCA.0000013536.27551.13

- Leppänen AS, Xu C, Parikka K, Eklund P, Sjöholm R, Brumer H, Tenkanen M, and Willför S. (2014). Targeted allylation and propargylation of galactose-containing polysaccharides in water. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;100:46-54. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.11.053 |

- Xu C, Spadiut O, Araújo AC, Nakhai A, and Brumer H. (2012). Chemo-enzymatic assembly of clickable cellulose surfaces via multivalent polysaccharides. ChemSusChem. 2012;5(4):661-5. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201100522 |

- Parikka K, Leppänen AS, Xu C, Pitkänen L, Eronen P, Osterberg M, Brumer H, Willför S, and Tenkanen M. (2012). Functional and anionic cellulose-interacting polymers by selective chemo-enzymatic carboxylation of galactose-containing polysaccharides. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13(8):2418-28. DOI:10.1021/bm300679a |

-

Mikkonen, K. S.; Parikka, K.; Suuronen, J.-P.; Ghafar, A.; Serimaa, R.; Tenkanen, M., (2014) Enzymatic oxidation as a potential new route to produce polysaccharide aerogels. RSC Advances. 4, 11884-11892. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3RA47440B

- Derikvand F, Yin DT, Barrett R, and Brumer H. (2016). Cellulose-Based Biosensors for Esterase Detection. Anal Chem. 2016;88(6):2989-93. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04661 |

- Ribeaucourt D, Bissaro B, Lambert F, Lafond M, and Berrin JG. (2022). Biocatalytic oxidation of fatty alcohols into aldehydes for the flavors and fragrances industry. Biotechnol Adv. 2022;56:107787. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107787 |

-

Rosatella AA, Simeonov SP, Frade RFM, Afonso CAM. (2011) 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) as a building block platform: Biological properties, synthesis and synthetic applications. Green Chem. 13, 754-93. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0GC00401D

- Cowley RE, Cirera J, Qayyum MF, Rokhsana D, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Dooley DM, and Solomon EI. (2016). Structure of the Reduced Copper Active Site in Preprocessed Galactose Oxidase: Ligand Tuning for One-Electron O(2) Activation in Cofactor Biogenesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(40):13219-13229. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b05792 |

- Thomas F, Gellon G, Gautier-Luneau I, Saint-Aman E, and Pierre JL. (2002). A structural and functional model of galactose oxidase: control of the one-electron oxidized active form through two differentiated phenolic arms in a tripodal ligand. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(16):3047-50. DOI:10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16<3047::AID-ANIE3047>3.0.CO;2-W |

- Wright C and Sykes AG. (2001). Interconversion of Cu(I) and Cu(II) forms of galactose oxidase: comparison of reduction potentials. J Inorg Biochem. 2001;85(4):237-43. DOI:10.1016/s0162-0134(01)00214-8 |

-

Itoh, S.; Taki, M.; Fukuzumi, S., (2000). Active site models for galactose oxidase and related enzymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 198, 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00209-X

-

Jazdzewski, B. A.; Tolman, W. B., (2000). Understanding the copper–phenoxyl radical array in galactose oxidase: contributions from synthetic modeling studies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 200-202, 633-685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00342-8

- Rogers MS, Tyler EM, Akyumani N, Kurtis CR, Spooner RK, Deacon SE, Tamber S, Firbank SJ, Mahmoud K, Knowles PF, Phillips SE, McPherson MJ, and Dooley DM. (2007). The stacking tryptophan of galactose oxidase: a second-coordination sphere residue that has profound effects on tyrosyl radical behavior and enzyme catalysis. Biochemistry. 2007;46(15):4606-18. DOI:10.1021/bi062139d |

-

Saysell, C. G.; Barna, T.; Borman, C. D.; Baron, A. J.; McPherson, M. J.; Sykes, A. G., P(1997). Properties of the Trp290His variant of Fusarium NRRL 2903 galactose oxidase: interactions of the GOasesemi state with different buffers, its redox activity and ability to bind azide. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2, 702-709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007750050186

- Baron AJ, Stevens C, Wilmot C, Seneviratne KD, Blakeley V, Dooley DM, Phillips SE, Knowles PF, and McPherson MJ. (1994). Structure and mechanism of galactose oxidase. The free radical site. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(40):25095-105. | Google Books | Open Library

-

Rogers, M. S.; Knowles, P. F.; Baron, A. J.; McPherson, M. J.; Dooley, D. M., (1998). Characterization of the active site of galactose oxidase and its active site mutational variants Y495F/H/K and W290H by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 275-276, 175-181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-1693(97)06142-2

- Whittaker JW (2005). The radical chemistry of galactose oxidase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433(1):227-39. DOI:10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.034 |

- Humphreys KJ, Mirica LM, Wang Y, and Klinman JP. (2009). Galactose oxidase as a model for reactivity at a copper superoxide center. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(13):4657-63. DOI:10.1021/ja807963e |

- Whittaker MM and Whittaker JW. (1993). Ligand interactions with galactose oxidase: mechanistic insights. Biophys J. 1993;64(3):762-72. DOI:10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81437-1 |

- Whittaker MM, Kersten PJ, Cullen D, and Whittaker JW. (1999). Identification of catalytic residues in glyoxal oxidase by targeted mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(51):36226-32. DOI:10.1074/jbc.274.51.36226 |

- Wang Y, DuBois JL, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, and Stack TD. (1998). Catalytic galactose oxidase models: biomimetic Cu(II)-phenoxyl-radical reactivity. Science. 1998;279(5350):537-40. DOI:10.1126/science.279.5350.537 |

-

Himo, F.; Eriksson, L. A.; Maseras, F.; Siegbahn, P. E. M., (2000). Catalytic Mechanism of Galactose Oxidase: A Theoretical Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 8031-8036. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja994527r

- Cleveland L, Coffman RE, Coon P, and Davis L. (1975). An investigation of the role of the copper in galactose oxidase. Biochemistry. 1975;14(6):1108-15. DOI:10.1021/bi00677a003 |

- Hamilton GA, Dyrkacz GR, and Libby RD. (1976). The involvement of superoxide and trivalent copper in the galactose oxidase reaction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1976;74:489-504. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4684-3270-1_42 |

-

Toftgaard Pedersen, A.; Birmingham, W. R.; Rehn, G.; Charnock, S. J.; Turner, N. J.; Woodley, J. M., (2015) Process Requirements of Galactose Oxidase Catalyzed Oxidation of Alcohols. Org. Process Res. Dev. 19, 1580-1589. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00278

- Forget SM, Xia FR, Hein JE, and Brumer H. (2020). Determination of biocatalytic parameters of a copper radical oxidase using real-time reaction progress monitoring. Org Biomol Chem. 2020;18(11):2076-2084. DOI:10.1039/c9ob02757b |

- Johnson HC, Zhang S, Fryszkowska A, Ruccolo S, Robaire SA, Klapars A, Patel NR, Whittaker AM, Huffman MA, and Strotman NA. (2021). Biocatalytic oxidation of alcohols using galactose oxidase and a manganese(III) activator for the synthesis of islatravir. Org Biomol Chem. 2021;19(7):1620-1625. DOI:10.1039/d0ob02395g |

- Ito N, Phillips SE, Yadav KD, and Knowles PF. (1994). Crystal structure of a free radical enzyme, galactose oxidase. J Mol Biol. 1994;238(5):794-814. DOI:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1335 |

- Ito N, Phillips SE, Stevens C, Ogel ZB, McPherson MJ, Keen JN, Yadav KD, and Knowles PF. (1991). Novel thioether bond revealed by a 1.7 A crystal structure of galactose oxidase. Nature. 1991;350(6313):87-90. DOI:10.1038/350087a0 |

- Rogers MS, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Firbank SJ, Halcrow MA, Dooley DM, Phillips SE, Knowles PF, and McPherson MJ. (2008). Cross-link formation of the cysteine 228-tyrosine 272 catalytic cofactor of galactose oxidase does not require dioxygen. Biochemistry. 2008;47(39):10428-39. DOI:10.1021/bi8010835 |

- Chaplin AK, Svistunenko DA, Hough MA, Wilson MT, Vijgenboom E, and Worrall JA. (2017). Active-site maturation and activity of the copper-radical oxidase GlxA are governed by a tryptophan residue. Biochem J. 2017;474(5):809-825. DOI:10.1042/BCJ20160968 |

- Faria CB, de Castro FF, Martim DB, Abe CAL, Prates KV, de Oliveira MAS, and Barbosa-Tessmann IP. (2019). Production of Galactose Oxidase Inside the Fusarium fujikuroi Species Complex and Recombinant Expression and Characterization of the Galactose Oxidase GaoA Protein from Fusarium subglutinans. Mol Biotechnol. 2019;61(9):633-649. DOI:10.1007/s12033-019-00190-6 |

- Mollerup F and Master E. (2016). Influence of a family 29 carbohydrate binding module on the recombinant production of galactose oxidase in Pichia pastoris. Data Brief. 2016;6:176-83. DOI:10.1016/j.dib.2015.11.032 |

-

Sousa AF, Vilela C, Fonseca AC, Matos M, Freire CSR, Gruter G-JM, Coelho JFJ, Silvestre AJD. (2015) Biobased polyesters and other polymers from 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid: a tribute to furan excellency. Polym Chem. 6, 5961-83. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5PY00686D