CAZypedia celebrates the life of Senior Curator Emeritus Harry Gilbert, a true giant in the field, who passed away in September 2025.

CAZypedia needs your help!

We have many unassigned pages in need of Authors and Responsible Curators. See a page that's out-of-date and just needs a touch-up? - You are also welcome to become a CAZypedian. Here's how.

Scientists at all career stages, including students, are welcome to contribute.

Learn more about CAZypedia's misson here and in this article. Totally new to the CAZy classification? Read this first.

Auxiliary Activity Family 13

This page is currently under construction. This means that the Responsible Curator has deemed that the page's content is not quite up to CAZypedia's standards for full public consumption. All information should be considered to be under revision and may be subject to major changes.

- Author: ^^^Glyn Hemsworth^^^ & ^^^Leila LoLeggio^^^

- Responsible Curator: ^^^Gideon Davies^^^

| Auxiliary Activity Family 13 | |

| Clan | Structurally related to AA9, AA10 & AA11 |

| Mechanism | lytic oxidase |

| Active site residues | mononuclear copper ion coordinated by the “histidine brace” |

| CAZy DB link | |

| https://www.cazy.org/AA13.html | |

Substrate specificities

The AA13 family represents the fourth family of Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases (LPMOs) that has been identified. Found in fungi, the first member of this family to be identified and characterised in the academic literature was isolated from Neurospora crassa by Vu et al [1]. While searching the Neurospora crassa genome for new putative LPMO sequences, they identified a sequence that appeared to code for an LPMO with a C-terminal CBM20 domain but lacked significant overall sequence similarity to other AA9, AA10 or AA11 LPMOs. Not long after Lo Leggio et al [2] also identified and characterised AA13 family members from Aspergilllus nidulans and Aspergillus oryzae using a similar approach. Prior to this, genes now known to code for AA13s were demonstrated to produce proteins capable of boosting α and β-amylase activity during starch, amylose and amylopectin degradation (WO2014197705A1).

Of the AA13s that have been biochemically characterised to date, activity has only been demonstrate on starch and related substrates [1, 2]. The expression of these enzymes has also been shown to be heavily unregulated during growth of A. nidulans on starch [3]. As for other LPMOs, AA13s utilise copper and an electron donor to oxidatively introduce chain breaks into the α-1,4-linked glucose polymers that form starch [1, 2]. AA13s specifically attack at the C1 position of the sugar ring forming oligosaccharide products with lactones at the reducing end which are then additionally hydrated to form aldonic acid terminated maltodextrins [2]. The C1 specificity suggests that these LPMOs should be able to oxidatively attack both the α-1,4- and α-1,6-linkages found in amylopectin [4]. Interestingly, AA13s are currently the only LPMOs characterised to date that act on a glucan polymer formed from anything other than β-1,4-linkages [5].

Kinetics and Mechanism

All LPMOs (AA9, AA10, AA11, & AA13) are copper dependent monooxygenases and there is considerable work ongoing in trying to elucidate their detailed reaction mechanism [6]. Starch, being an α-1,4-linked substrate, poses a different challenge for AA13s to be able to oxidatively attack at the C1 carbon. Whether there is a significant difference in mechanism required in order to oxidise starch is currently unclear.

Performing kinetic measurements on LPMOs has been notoriously difficult. Several key aspects of AA13 biochemistry have been observed however. The A. nidulans AA13 showed significant synergy with a β-amylase during degradation assays using retrograded starch as the substrate. The combined action of these enzymes resulted in >100-fold increase in the release of maltose compared to β-amylase acting alone, representing one of the most significant boosting activities observed so far for any LPMO [2]. Also highlighted in this study was the importance of the reducing agent used to activate the enzyme with cysteine providing greater activity than ascorbate which is typically used to activate LPMOs. Vu et al [1] also showed that cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH composed of AA3 and AA8 domains) represents a good activating partner for AA13s as has been observed for AA9s. The importance of the CBM20 module for AA13 activity has also been highlighted. The A. oryzae AA13, which naturally lacks a CBM, did not appear to be active in assays on starch while the CBM20 appended A.nidulans enzyme showed clear activity [2]. Indeed the presence of the CBM20 domain has been demonstrated to confer typical starch and β-cyclodextrin binding properties to AA13s and is suggested to mediate most of the substrate binding properties of this family of enzymes [7].

Three-dimensional structures

The core fold of the AA13 structure is similar to all other LPMOs (AA9, AA10, & AA11) representing a β-sandwich immunoglobulin like fold [2]. There are some significant structural differences compared to the other families however. Firstly, the AA13 structure reveals additional helical secondary structure elements that are not found in other LPMOs (Figure 1). The most prominent difference however is surrounding the copper active site. Where in other LPMOs, the copper histidine brace is found at the centre of a flat or slightly concave surface (AA9, AA10, & AA11), a distinct groove can be observed passing over the active site of AA13 (Figure 1). This is an adaptation that is thought to be necessary to accommodate the helical structure of an amylopectin substrate. Despite significant efforts, it has not been possible to determine an oligosaccharide bound structure for an AA13 which would be particularly beneficial to delineating the adaptions necessary to allow activity on an α-1,4-linked substrate [8].

Catalytic Residues

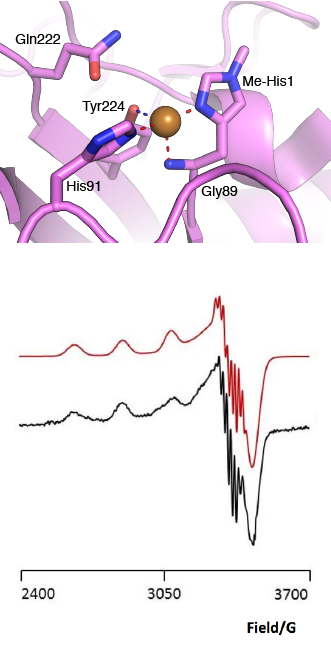

The “histidine brace” motif is used to bind the active site copper in AA13 [2], as it is for all other LPMOs studied to date (AA9, AA10 & AA11) [9]. This motif sees the amino group and imidazole side chain of the N-terminal histidine, together with the imidazole group of a second histidine, directly coordinate the copper ion in a T-shaped geometry. For AA13s, one axial position is occupied by a tyrosine on one side of the copper ion, with a loop containing a glycine approaching near to the copper on the other side (Figure 2, top) [2]. In AA10s and AA11s alanine in this position has been suggested as a possible important factor in distorting the arrangement of water molecules around the active site which may have mechanistic consequences in these families [10, 11]. An interesting feature of the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum observed for the A. nidulans and A. oryzae AA13s was the presence of superhyperfine coupling in the spectrum (Figure 2, bottom) [2]. This was indicative of a potentially more ordered active site arrangement around the copper which may be the result of structural changes that are required in order to oxidise starch and may imply that AA13s are not subject to the substrate controlled activation mechanism suggested for AA9s [12].

Family Firsts

- First family member identified

- AA13 from N. crassa [1].

- First demonstration of oxidative cleavage

- The N. crassa AA13 was shown to produce oxidised malto-oligosaccharides in the presence of oxygen and reducing agents [1].

- First 3-D structure

- AA13 from A. oryzae with Cu+ 4OPB [2]

References

- Vu VV, Beeson WT, Span EA, Farquhar ER, and Marletta MA. (2014). A family of starch-active polysaccharide monooxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(38):13822-7. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1408090111 |

- Lo Leggio L, Simmons TJ, Poulsen JC, Frandsen KE, Hemsworth GR, Stringer MA, von Freiesleben P, Tovborg M, Johansen KS, De Maria L, Harris PV, Soong CL, Dupree P, Tryfona T, Lenfant N, Henrissat B, Davies GJ, and Walton PH. (2015). Structure and boosting activity of a starch-degrading lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5961. DOI:10.1038/ncomms6961 |

-

Nekiunaite, L., Arntzen, M.Ø., Svensson, B., Vaaje-Kolstad, G., Abou Hachem, M. (2016) Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases and other oxidative enzymes are abundantly secreted by Aspergillus nidulans grown on different starches. Biotechnology for Biofuels. 9, 187 [1]

- Vu VV and Marletta MA. (2016). Starch-degrading polysaccharide monooxygenases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(14):2809-19. DOI:10.1007/s00018-016-2251-9 |

- Walton PH and Davies GJ. (2016). On the catalytic mechanisms of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;31:195-207. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.04.001 |

- Nekiunaite L, Isaksen T, Vaaje-Kolstad G, and Abou Hachem M. (2016). Fungal lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases bind starch and β-cyclodextrin similarly to amylolytic hydrolases. FEBS Lett. 2016;590(16):2737-47. DOI:10.1002/1873-3468.12293 |

- Frandsen KE, Poulsen JC, Tovborg M, Johansen KS, and Lo Leggio L. (2017). Learning from oligosaccharide soaks of crystals of an AA13 lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase: crystal packing, ligand binding and active-site disorder. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2017;73(Pt 1):64-76. DOI:10.1107/S2059798316019641 |

- Vaaje-Kolstad G, Forsberg Z, Loose JS, Bissaro B, and Eijsink VG. (2017). Structural diversity of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;44:67-76. DOI:10.1016/j.sbi.2016.12.012 |

- Frandsen KE, Simmons TJ, Dupree P, Poulsen JC, Hemsworth GR, Ciano L, Johnston EM, Tovborg M, Johansen KS, von Freiesleben P, Marmuse L, Fort S, Cottaz S, Driguez H, Henrissat B, Lenfant N, Tuna F, Baldansuren A, Davies GJ, Lo Leggio L, and Walton PH. (2016). The molecular basis of polysaccharide cleavage by lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12(4):298-303. DOI:10.1038/nchembio.2029 |

- Bertini L, Breglia R, Lambrughi M, Fantucci P, De Gioia L, Borsari M, Sola M, Bortolotti CA, and Bruschi M. (2018). Catalytic Mechanism of Fungal Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases Investigated by First-Principles Calculations. Inorg Chem. 2018;57(1):86-97. DOI:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02005 |

- Kim S, Ståhlberg J, Sandgren M, Paton RS, and Beckham GT. (2014). Quantum mechanical calculations suggest that lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases use a copper-oxyl, oxygen-rebound mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(1):149-54. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1316609111 |

- Forsberg Z, Mackenzie AK, Sørlie M, Røhr ÅK, Helland R, Arvai AS, Vaaje-Kolstad G, and Eijsink VG. (2014). Structural and functional characterization of a conserved pair of bacterial cellulose-oxidizing lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(23):8446-51. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1402771111 |

- Borisova AS, Isaksen T, Dimarogona M, Kognole AA, Mathiesen G, Várnai A, Røhr ÅK, Payne CM, Sørlie M, Sandgren M, and Eijsink VG. (2015). Structural and Functional Characterization of a Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenase with Broad Substrate Specificity. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(38):22955-69. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M115.660183 |

- Span EA, Suess DLM, Deller MC, Britt RD, and Marletta MA. (2017). The Role of the Secondary Coordination Sphere in a Fungal Polysaccharide Monooxygenase. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12(4):1095-1103. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.7b00016 |

- Forsberg Z, Bissaro B, Gullesen J, Dalhus B, Vaaje-Kolstad G, and Eijsink VGH. (2018). Structural determinants of bacterial lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase functionality. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(4):1397-1412. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M117.817130 |