CAZypedia celebrates the life of Senior Curator Emeritus Harry Gilbert, a true giant in the field, who passed away in September 2025.

CAZypedia needs your help!

We have many unassigned pages in need of Authors and Responsible Curators. See a page that's out-of-date and just needs a touch-up? - You are also welcome to become a CAZypedian. Here's how.

Scientists at all career stages, including students, are welcome to contribute.

Learn more about CAZypedia's misson here and in this article. Totally new to the CAZy classification? Read this first.

Difference between revisions of "Carbohydrate Binding Module Family 13"

| (30 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- RESPONSIBLE CURATORS: Please replace the {{UnderConstruction}} tag below with {{CuratorApproved}} when the page is ready for wider public consumption --> | <!-- RESPONSIBLE CURATORS: Please replace the {{UnderConstruction}} tag below with {{CuratorApproved}} when the page is ready for wider public consumption --> | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{CuratorApproved}} |

* [[Author]]: [[User:Lauren McKee|Lauren McKee]] and [[User:Scott Mazurkewich|Scott Mazurkewich]] | * [[Author]]: [[User:Lauren McKee|Lauren McKee]] and [[User:Scott Mazurkewich|Scott Mazurkewich]] | ||

* [[Responsible Curator]]: [[User:Lauren McKee|Lauren McKee]] | * [[Responsible Curator]]: [[User:Lauren McKee|Lauren McKee]] | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<!-- This is the end of the table --> | <!-- This is the end of the table --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Ligand specificities == | == Ligand specificities == | ||

| − | The first identified CBM13 domains were in plant lectins like ricin and agglutinin, and were found to bind galactose residues <cite>Fujimoto2013</cite>. The domains were later found to be common within many CAZymes, especially glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases. Binding to galactose, lactose, and agar is common in the family <cite>Cui2018</cite>, and binding to galacto- | + | The first identified CBM13 domains were in plant [[Carbohydrate-binding_modules#Blurred Lines: CBMs, Lectins and Outliers|lectins]] like the ricin toxin and agglutinin, and were found to bind galactose residues <cite>Fujimoto2013</cite>. The domains were later found to be common within many CAZymes, especially glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases. Binding to galactose, lactose, and agar is common in the family <cite>Cui2018</cite>, and binding to galacto-oligosaccharides of various different linkages has been observed <cite>Ichinose2006 Jiang2012</cite>. Some structural studies have shown the CBM13 binding sites can accommodate either the non-reducing end galactose or the reducing end glucose in lactose, showing remarkable plasticity in binding preference <cite>Notenboom2002</cite>. |

| − | There are also many examples of xylan-binding CBM13 domains <cite>Garrido2022 Hagiwara2022</cite>. Here there is evidence of mid-chain binding to longer oligosaccharides, and that xylopentaose can bind to two binding sites simultaneously, wrapping about the CBM13 | + | There are also many examples of xylan-binding CBM13 domains <cite>Garrido2022 Hagiwara2022</cite>. Here, there is evidence of mid-chain binding to longer oligosaccharides, and that xylopentaose can bind to two binding sites simultaneously, wrapping about the CBM13 domains to do so <cite>Notenboom2002</cite>. Multiple binding sites are often functional within CBM13 domains, with the α site seemingly being the strongest <cite>Scharpf2002 Fujimoto2004</cite>. Avid binding has been demonstrated for laminarin, by a CBM13 domain found in a β-1,3-glucanase <cite>Tamashiro2012</cite>. More recently, binding to alginate has also been demonstrated <cite>Lian2024</cite> and a CBM13 domain was identified in a cycloisomaltotetraose enzyme <cite>Fujita2021</cite>. |

== Structural Features == | == Structural Features == | ||

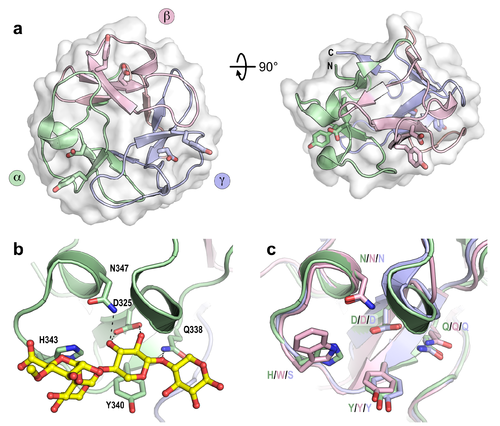

| − | CBM13 proteins are | + | [[File: Cbm13 overview.png|thumb|right|500px|'''Figure 1. Structure of the CBM13 domain in the multidomain protein Xyn10A from ''Streptomyces olivaceoviridis'' E-86.''' a) The overall structure with the subdomains distinctly coloured and its ligand binding tyrosine and aspartate residues of each subdomain shown as sticks (PDB accession [{{PDBlink}}1xyf 1XYF]). b) The binding site found in the α-subdomain of the CBM13 domain in complex with 2<sup>3</sup>-4-''O''-methyl-α-D-glucuronosyl-xylotriose (MeGlcUA-X3, PDB accession [{{PDBlink}}1v6x 1V6X]). c) Overlay of the subdomains showing sequence conservation within the binding sites. Single letter residue codes are coloured based on the subdomains shown in panel a) and are labelled for subdomains ⍺/β/γ, in that order.]] |

| + | CBM13 proteins are [[Carbohydrate-binding_modules#Types|type B]] or [[Carbohydrate-binding_modules#Types|type C]] CBMs, comprising 3 internal subdomains (α, β, and γ), each approximately 40 residues in length, which fold in similar ways around a pseudo-3-fold axis, giving rise to a β-trefoil tertiary structure ('''Figure 1'''), as is also common for plant lectins. The ligand binding site in each subdomain is found in a surface exposed pocket, where binding is principally facilitated by tyrosine and aspartate residues found conserved within each subdomain. The binding sites are designated as α, β, and γ, referring to the subdomain from which they are found. The same naming system has been used for the other multivalent β-trefoil members families [[CBM42]] and [[CBM92]], which share the same modular structure as CBM13 domains. | ||

== Functionalities == | == Functionalities == | ||

| − | + | Carbohydrate Binding Module family 13 has a rich history. The earliest known examples were biochemically characterised prior to their annotation as CBM13 domains. These were shown to be xylan binders increasing substrate affinity of industrial xylan-degrading enzymes <cite>Irwin1994</cite>, yet they often proved to be non-essential in xylan hydrolysing <cite>Black1995</cite> and wood pulp bleaching applications <cite>Morris1998 Leskinen2002</cite>. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Bioinformatic analysis has revealed a strong cooccurrence of CBM13 and [[GH43]] modules, with subfamily [[GH43]]_7 enzymes apparently all containing a CBM13 domain <cite>Mewis2016</cite>. In that enzyme subfamily, the α-L-arabinofuranosidase AbfB from ''Streptomyces lividans'' carries a xylan-binding CBM13 domain <cite>Vincent1997</cite>, as does an endo-β-1,4-xylanase from ''Bacteroides intestinalis'' <cite>Pereira2021</cite>. CBM13 domains are also abundant in β-agarases, found in enzyme families [[GH16]], [[GH39]], [[GH50]], [[GH86]], and [[GH118]] <cite>Veerakumar2018</cite>. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | Diverse other examples have shown that a CBM13 domain binding to the substrate of an appended glycoside hydrolase module does lead to activity potentiation through enhanced substrate [[Carbohydrate-binding_modules#Functional Roles of CBMs|proximity]] effects, such as in a [[GH16]] agarase from ''Gilvimarinus agarilyticus'' JEA5 <cite>Lee2018</cite> and a [[GH5]]_35 xylanase from ''Paenibacillus'' sp. H2C <cite>Hagiwara2022</cite>. The enzyme endo-β-agarase I from ''Microbulbifer thermotolerans'' JAMB-A94 was engineered by fusing the [[GH16]] catalytic module to a CBM13 domain derived from the agarolytic marine bacterium ''Catenovulum agarivorans'' <cite>Cui2014</cite>, leading to a substantial increase in agar binding and hydrolysis in the fusion enzyme <cite>Alkotaini2016</cite>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Reaction product structure can sometimes be affected by the action of a CBM domain. In the case of the PelQ1 pectate lyase from ''Saccharobesus litoralis'', inclusion of the native CBM13 domain in the recombinant protein promoted the formation of a dimer from polygalacturonate, whereas the enzyme without CBM produced a mixture of oligosaccharides dominated by an unsaturated trimer <cite>Lian2024</cite>. The CBM13 domain from an ''Agarivorans'' sp. L11 alginate lyase apparently improves both the catalytic efficiency and heat tolerance of the enzyme, as well as increasing the proportion of disaccharides in the final reaction product mix <cite>Li2015</cite>. It is proposed that a CBM13 also contributes to controlling product length in cycloisomaltotetraose-forming CI4Tase enzymes <cite>Fujita2021</cite>. | ||

== Family Firsts == | == Family Firsts == | ||

| − | ;First Identified | + | ;First Identified:The first reported characterization of a protein containing a CBM13 domain was xylanase A from ''Streptomyces lividans'' (''Sl''XynA) <cite>Morosoli1986</cite>. At that time, the CBM had not been distinguished from the xylanase domain within the gene product. Subsequent gene sequencing and sequence alignment studies demonstrated that the domain was distinct from other CBM families <cite>Dupont1998</cite> and was later categorised as CBM family 13 <cite>Tomme1998</cite>. |

| − | : | + | ;First Structural Characterization:The structure of the first CBM13 member, defined as a carbohydrate active enzyme encoded with the CBM domain, was Xyn10A from ''Streptomyces olivaceoviridis'' E-86 (''So''XynA; <cite>Fujimoto2000</cite>; PDB: [{{PDBlink}}1xyf 1XYF]). The first structures of a CBM13 in complex with ligands were reported with ''So''Xyn10A <cite>Fujimoto2002</cite> followed very soon after by complex structures with Xyn10A from ''Streptomyces lividans'' (''Sl''Xyn10A; <cite>Notenboom2002</cite>). |

| − | ;First Structural Characterization | ||

| − | : | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

#Lian2024 pmid=38340525 | #Lian2024 pmid=38340525 | ||

#Fujita2021 pmid=34661636 | #Fujita2021 pmid=34661636 | ||

| + | #Irwin1994 pmid=8161173 | ||

| + | #Black1995 pmid=7717975 | ||

| + | #Morris1998 pmid=9572948 | ||

| + | #Leskinen2002 pmid=15650852 | ||

| + | #Mewis2016 pmid=26729713 | ||

| + | #Vincent1997 pmid=9148759 | ||

| + | #Pereira2021 pmid=33469030 | ||

| + | #Veerakumar2018 pmid=30333947 | ||

| + | #Lee2018 pmid=29551022 | ||

| + | #Hagiwara2022 pmid=36352459 | ||

| + | #Cui2014 pmid=24824021 | ||

| + | #Alkotaini2016 pmid=27702474 | ||

| + | #Li2015 pmid=25837818 | ||

| + | #Morosoli1986 pmid=3827815 | ||

| + | #Dupont1998 pmid=9461488 | ||

| + | #Tomme1998 pmid=9792516 | ||

</biblio> | </biblio> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:23, 31 October 2025

This page has been approved by the Responsible Curator as essentially complete. CAZypedia is a living document, so further improvement of this page is still possible. If you would like to suggest an addition or correction, please contact the page's Responsible Curator directly by e-mail.

| CAZy DB link | |

| https://www.cazy.org/CBM13.html |

Ligand specificities

The first identified CBM13 domains were in plant lectins like the ricin toxin and agglutinin, and were found to bind galactose residues [1]. The domains were later found to be common within many CAZymes, especially glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases. Binding to galactose, lactose, and agar is common in the family [2], and binding to galacto-oligosaccharides of various different linkages has been observed [3, 4]. Some structural studies have shown the CBM13 binding sites can accommodate either the non-reducing end galactose or the reducing end glucose in lactose, showing remarkable plasticity in binding preference [5].

There are also many examples of xylan-binding CBM13 domains [6, 7]. Here, there is evidence of mid-chain binding to longer oligosaccharides, and that xylopentaose can bind to two binding sites simultaneously, wrapping about the CBM13 domains to do so [5]. Multiple binding sites are often functional within CBM13 domains, with the α site seemingly being the strongest [8, 9]. Avid binding has been demonstrated for laminarin, by a CBM13 domain found in a β-1,3-glucanase [10]. More recently, binding to alginate has also been demonstrated [11] and a CBM13 domain was identified in a cycloisomaltotetraose enzyme [12].

Structural Features

CBM13 proteins are type B or type C CBMs, comprising 3 internal subdomains (α, β, and γ), each approximately 40 residues in length, which fold in similar ways around a pseudo-3-fold axis, giving rise to a β-trefoil tertiary structure (Figure 1), as is also common for plant lectins. The ligand binding site in each subdomain is found in a surface exposed pocket, where binding is principally facilitated by tyrosine and aspartate residues found conserved within each subdomain. The binding sites are designated as α, β, and γ, referring to the subdomain from which they are found. The same naming system has been used for the other multivalent β-trefoil members families CBM42 and CBM92, which share the same modular structure as CBM13 domains.

Functionalities

Carbohydrate Binding Module family 13 has a rich history. The earliest known examples were biochemically characterised prior to their annotation as CBM13 domains. These were shown to be xylan binders increasing substrate affinity of industrial xylan-degrading enzymes [13], yet they often proved to be non-essential in xylan hydrolysing [14] and wood pulp bleaching applications [15, 16].

Bioinformatic analysis has revealed a strong cooccurrence of CBM13 and GH43 modules, with subfamily GH43_7 enzymes apparently all containing a CBM13 domain [17]. In that enzyme subfamily, the α-L-arabinofuranosidase AbfB from Streptomyces lividans carries a xylan-binding CBM13 domain [18], as does an endo-β-1,4-xylanase from Bacteroides intestinalis [19]. CBM13 domains are also abundant in β-agarases, found in enzyme families GH16, GH39, GH50, GH86, and GH118 [20].

Diverse other examples have shown that a CBM13 domain binding to the substrate of an appended glycoside hydrolase module does lead to activity potentiation through enhanced substrate proximity effects, such as in a GH16 agarase from Gilvimarinus agarilyticus JEA5 [21] and a GH5_35 xylanase from Paenibacillus sp. H2C [7]. The enzyme endo-β-agarase I from Microbulbifer thermotolerans JAMB-A94 was engineered by fusing the GH16 catalytic module to a CBM13 domain derived from the agarolytic marine bacterium Catenovulum agarivorans [22], leading to a substantial increase in agar binding and hydrolysis in the fusion enzyme [23].

Reaction product structure can sometimes be affected by the action of a CBM domain. In the case of the PelQ1 pectate lyase from Saccharobesus litoralis, inclusion of the native CBM13 domain in the recombinant protein promoted the formation of a dimer from polygalacturonate, whereas the enzyme without CBM produced a mixture of oligosaccharides dominated by an unsaturated trimer [11]. The CBM13 domain from an Agarivorans sp. L11 alginate lyase apparently improves both the catalytic efficiency and heat tolerance of the enzyme, as well as increasing the proportion of disaccharides in the final reaction product mix [24]. It is proposed that a CBM13 also contributes to controlling product length in cycloisomaltotetraose-forming CI4Tase enzymes [12].

Family Firsts

- First Identified

- The first reported characterization of a protein containing a CBM13 domain was xylanase A from Streptomyces lividans (SlXynA) [25]. At that time, the CBM had not been distinguished from the xylanase domain within the gene product. Subsequent gene sequencing and sequence alignment studies demonstrated that the domain was distinct from other CBM families [26] and was later categorised as CBM family 13 [27].

- First Structural Characterization

- The structure of the first CBM13 member, defined as a carbohydrate active enzyme encoded with the CBM domain, was Xyn10A from Streptomyces olivaceoviridis E-86 (SoXynA; [28]; PDB: 1XYF). The first structures of a CBM13 in complex with ligands were reported with SoXyn10A [29] followed very soon after by complex structures with Xyn10A from Streptomyces lividans (SlXyn10A; [5]).

References

- Fujimoto Z (2013). Structure and function of carbohydrate-binding module families 13 and 42 of glycoside hydrolases, comprising a β-trefoil fold. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77(7):1363-71. DOI:10.1271/bbb.130183 |

- Cui X, Jiang Y, Chang L, Meng L, Yu J, Wang C, and Jiang X. (2018). Heterologous expression of an agarase gene in Bacillus subtilis, and characterization of the agarase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;120(Pt A):657-664. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.07.118 |

- Ichinose H, Kuno A, Kotake T, Yoshida M, Sakka K, Hirabayashi J, Tsumuraya Y, and Kaneko S. (2006). Characterization of an exo-beta-1,3-galactanase from Clostridium thermocellum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(5):3515-23. DOI:10.1128/AEM.72.5.3515-3523.2006 |

- Jiang D, Fan J, Wang X, Zhao Y, Huang B, Liu J, and Zhang XC. (2012). Crystal structure of 1,3Gal43A, an exo-β-1,3-galactanase from Clostridium thermocellum. J Struct Biol. 2012;180(3):447-57. DOI:10.1016/j.jsb.2012.08.005 |

- Notenboom V, Boraston AB, Williams SJ, Kilburn DG, and Rose DR. (2002). High-resolution crystal structures of the lectin-like xylan binding domain from Streptomyces lividans xylanase 10A with bound substrates reveal a novel mode of xylan binding. Biochemistry. 2002;41(13):4246-54. DOI:10.1021/bi015865j |

- Garrido MM, Piccinni FE, Landoni M, Peña MJ, Topalian J, Couto A, Wirth SA, Urbanowicz BR, and Campos E. (2022). Insights into the xylan degradation system of Cellulomonas sp. B6: biochemical characterization of rCsXyn10A and rCsAbf62A. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106(13-16):5035-5049. DOI:10.1007/s00253-022-12061-3 |

- Hagiwara Y, Okeda T, Okuda K, Yatsunami R, and Nakamura S. (2022). Characterization of a xylanase belonging to the glycoside hydrolase family 5 subfamily 35 from Paenibacillus sp. H2C. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2022;87(1):54-62. DOI:10.1093/bbb/zbac175 |

- Hagiwara Y, Okeda T, Okuda K, Yatsunami R, and Nakamura S. (2022). Characterization of a xylanase belonging to the glycoside hydrolase family 5 subfamily 35 from Paenibacillus sp. H2C. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2022;87(1):54-62. DOI:10.1093/bbb/zbac175 |

- Schärpf M, Connelly GP, Lee GM, Boraston AB, Warren RA, and McIntosh LP. (2002). Site-specific characterization of the association of xylooligosaccharides with the CBM13 lectin-like xylan binding domain from Streptomyces lividans xylanase 10A by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2002;41(13):4255-63. DOI:10.1021/bi015866b |

- Fujimoto Z, Kaneko S, Kuno A, Kobayashi H, Kusakabe I, and Mizuno H. (2004). Crystal structures of decorated xylooligosaccharides bound to a family 10 xylanase from Streptomyces olivaceoviridis E-86. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(10):9606-14. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M312293200 |

- Tamashiro T, Tanabe Y, Ikura T, Ito N, and Oda M. (2012). Critical roles of Asp270 and Trp273 in the α-repeat of the carbohydrate-binding module of endo-1,3-β-glucanase for laminarin-binding avidity. Glycoconj J. 2012;29(1):77-85. DOI:10.1007/s10719-011-9366-x |

- Lian MQ, Furusawa G, and Teh AH. (2024). Trigalacturonate-producing pectate lyase PelQ1 from Saccharobesus litoralis with unique exolytic activity. Carbohydr Res. 2024;536:109045. DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2024.109045 |

- Fujita A, Kawashima A, Noguchi Y, Hirose S, Kitagawa N, Watanabe H, Mori T, Nishimoto T, Aga H, Ushio S, and Yamamoto K. (2021). Cloning of the cycloisomaltotetraose-forming enzymes using whole genome sequence analyses of Agreia sp. D1110 and Microbacterium trichothecenolyticum D2006. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2021;86(1):68-77. DOI:10.1093/bbb/zbab181 |

- Irwin D, Jung ED, and Wilson DB. (1994). Characterization and sequence of a Thermomonospora fusca xylanase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60(3):763-70. DOI:10.1128/aem.60.3.763-770.1994 |

- Black GW, Hazlewood GP, Millward-Sadler SJ, Laurie JI, and Gilbert HJ. (1995). A modular xylanase containing a novel non-catalytic xylan-specific binding domain. Biochem J. 1995;307 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1):191-5. DOI:10.1042/bj3070191 |

- Morris DD, Gibbs MD, Chin CW, Koh MH, Wong KK, Allison RW, Nelson PJ, and Bergquist PL. (1998). Cloning of the xynB gene from Dictyoglomus thermophilum Rt46B.1 and action of the gene product on kraft pulp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64(5):1759-65. DOI:10.1128/AEM.64.5.1759-1765.1998 |

- Leskinen S, Mäntylä A, Fagerström R, Vehmaanperä J, Lantto R, Paloheimo M, and Suominen P. (2005). Thermostable xylanases, Xyn10A and Xyn11A, from the actinomycete Nonomuraea flexuosa: isolation of the genes and characterization of recombinant Xyn11A polypeptides produced in Trichoderma reesei. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67(4):495-505. DOI:10.1007/s00253-004-1797-x |

- Mewis K, Lenfant N, Lombard V, and Henrissat B. (2016). Dividing the Large Glycoside Hydrolase Family 43 into Subfamilies: a Motivation for Detailed Enzyme Characterization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82(6):1686-1692. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03453-15 |

- Vincent P, Shareck F, Dupont C, Morosoli R, and Kluepfel D. (1997). New alpha-L-arabinofuranosidase produced by Streptomyces lividans: cloning and DNA sequence of the abfB gene and characterization of the enzyme. Biochem J. 1997;322 ( Pt 3)(Pt 3):845-52. DOI:10.1042/bj3220845 |

- Pereira GV, Abdel-Hamid AM, Dutta S, D'Alessandro-Gabazza CN, Wefers D, Farris JA, Bajaj S, Wawrzak Z, Atomi H, Mackie RI, Gabazza EC, Shukla D, Koropatkin NM, and Cann I. (2021). Degradation of complex arabinoxylans by human colonic Bacteroidetes. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):459. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-20737-5 |

- Veerakumar S and Manian RP. (2018). Recombinant β-agarases: insights into molecular, biochemical, and physiochemical characteristics. 3 Biotech. 2018;8(10):445. DOI:10.1007/s13205-018-1470-1 |

- Lee Y, Jo E, Lee YJ, Hettiarachchi SA, Park GH, Lee SJ, Heo SJ, Kang DH, and Oh C. (2018). A Novel Glycosyl Hydrolase Family 16 β-Agarase from the Agar-Utilizing Marine Bacterium Gilvimarinus agarilyticus JEA5: the First Molecular and Biochemical Characterization of Agarase in Genus Gilvimarinus. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;28(5):776-783. DOI:10.4014/jmb.1709.09050 |

- Cui F, Dong S, Shi X, Zhao X, and Zhang XH. (2014). Overexpression and characterization of a novel thermostable β-agarase YM01-3, from marine bacterium Catenovulum agarivorans YM01(T). Mar Drugs. 2014;12(5):2731-47. DOI:10.3390/md12052731 |

- Alkotaini B, Han NS, and Kim BS. (2016). Enhanced catalytic efficiency of endo-β-agarase I by fusion of carbohydrate-binding modules for agar prehydrolysis. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2016;93-94:142-149. DOI:10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.08.010 |

- Li S, Yang X, Bao M, Wu Y, Yu W, and Han F. (2015). Family 13 carbohydrate-binding module of alginate lyase from Agarivorans sp. L11 enhances its catalytic efficiency and thermostability, and alters its substrate preference and product distribution. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015;362(10). DOI:10.1093/femsle/fnv054 |

- Morosoli R, Bertrand JL, Mondou F, Shareck F, and Kluepfel D. (1986). Purification and properties of a xylanase from Streptomyces lividans. Biochem J. 1986;239(3):587-92. DOI:10.1042/bj2390587 |

- Dupont C, Roberge M, Shareck F, Morosoli R, and Kluepfel D. (1998). Substrate-binding domains of glycanases from Streptomyces lividans: characterization of a new family of xylan-binding domains. Biochem J. 1998;330 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1):41-5. DOI:10.1042/bj3300041 |

- Tomme P, Boraston A, McLean B, Kormos J, Creagh AL, Sturch K, Gilkes NR, Haynes CA, Warren RA, and Kilburn DG. (1998). Characterization and affinity applications of cellulose-binding domains. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1998;715(1):283-96. DOI:10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00053-x |