CAZypedia celebrates the life of Senior Curator Emeritus Harry Gilbert, a true giant in the field, who passed away in September 2025.

CAZypedia needs your help!

We have many unassigned pages in need of Authors and Responsible Curators. See a page that's out-of-date and just needs a touch-up? - You are also welcome to become a CAZypedian. Here's how.

Scientists at all career stages, including students, are welcome to contribute.

Learn more about CAZypedia's misson here and in this article. Totally new to the CAZy classification? Read this first.

Difference between revisions of "Glycoside Hydrolase Family 73"

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

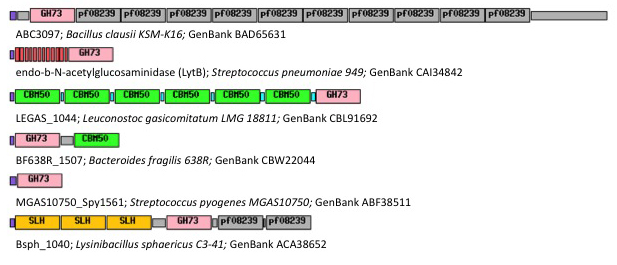

GH73 enzymes are mostly surface-located and often exhibit repeated sequences that could be involved in bacterial cell-wall binding (figure 1). Unknown repeated domains are appended for instance to LytD and LytG from ''Bacillus subtilis'' <cite>Rashid1995 Horsburgh2003</cite>, AcmB from ''Lactococcus lactis'' <cite>Huard2003</cite> and Auto from ''L. monocytogene'' <cite>Bublitz2009</cite>. Some of these repeated domains have been identified such as the carbohydrate-binding modules of family CBM50 (also known as LysM domains) appended to AcmA of ''Lactococcus lactis'' <cite>Inagaki2009</cite>, AltA from ''Enterococcus faecalis'' <cite>Eckert2006</cite> and Mur2-Mur2 from ''Enterococcus hirae'' <cite>Eckert2007</cite>. | GH73 enzymes are mostly surface-located and often exhibit repeated sequences that could be involved in bacterial cell-wall binding (figure 1). Unknown repeated domains are appended for instance to LytD and LytG from ''Bacillus subtilis'' <cite>Rashid1995 Horsburgh2003</cite>, AcmB from ''Lactococcus lactis'' <cite>Huard2003</cite> and Auto from ''L. monocytogene'' <cite>Bublitz2009</cite>. Some of these repeated domains have been identified such as the carbohydrate-binding modules of family CBM50 (also known as LysM domains) appended to AcmA of ''Lactococcus lactis'' <cite>Inagaki2009</cite>, AltA from ''Enterococcus faecalis'' <cite>Eckert2006</cite> and Mur2-Mur2 from ''Enterococcus hirae'' <cite>Eckert2007</cite>. | ||

| − | [[Image:Diapositive1recadree.jpg | + | [[Image:Diapositive1recadree.jpg|left|'''Figure 2.''' Ribbon diagram of Auto structure (orange) and its surface, superimposed on FlgJ structure (green).]] |

Revision as of 01:40, 27 October 2010

This page is currently under construction. This means that the Responsible Curator has deemed that the page's content is not quite up to CAZypedia's standards for full public consumption. All information should be considered to be under revision and may be subject to major changes.

- Author: ^^^Florence Vincent^^^

- Responsible Curator: ^^^Bernard Henrissat^^^

| Glycoside Hydrolase Family GH73 | |

| Clan | none, α+β "lysozyme fold" |

| Mechanism | not known |

| Active site residues | partially known |

| CAZy DB link | |

| https://www.cazy.org/GH73.html | |

Substrate specificities

Family GH73 contains bacterial and viral glycoside hydrolases. Most of the enzymes of this family cleave the β-1,4-glycosidic linkage between N-acetylglucosaminyl (NAG) and N-acetylmuramyl (NAM) moieties in the carbohydrate backbone of bacterial peptidoglycans. Because of their cleavage specificity, they are commonly described as β-N-acetylglucosaminidases. The enzymes from family GH73 are mainly involved in daughter cell separation during vegetative growth, and they often hydrolyze the septum after cell division (Acp from Clostridium perfringens [1] AltA from Enterococcus faecalis [2]). Occasionally GH73 enzymes are used during host-cell invasion such as the virulence-associated peptidoglycan hydrolase Auto from Listeria monocytogene [3]. GH73 enzymes are mostly surface-located and often exhibit repeated sequences that could be involved in bacterial cell-wall binding (figure 1). Unknown repeated domains are appended for instance to LytD and LytG from Bacillus subtilis [4, 5], AcmB from Lactococcus lactis [6] and Auto from L. monocytogene [3]. Some of these repeated domains have been identified such as the carbohydrate-binding modules of family CBM50 (also known as LysM domains) appended to AcmA of Lactococcus lactis [7], AltA from Enterococcus faecalis [2] and Mur2-Mur2 from Enterococcus hirae [8].

Kinetics and Mechanism

No kinetic parameters have been determined for any enzyme of the GH73 family, as the production of synthetic peptidoglycan substrates remains a challenge.

Three-dimensional structures

Crystal structures of GH73 are available and have been reported simultaneously, namely FlgJ from Sphingomonas sp. (SPH1045-C) [9] and Auto a virulence associated peptigoglycan hydrolase from Listeria monocytogenes [3]. The two GH73 show the same fold, with two subdomains consisting of a β-lobe and an α-lobe that together create an extended substrate binding groove (Figure 2). With a typical lysozyme (α+β) fold, the catalytic domain of Auto is structurally related to the catalytic domain of Slt70 from E. coli [10], the family GH19 chitinases and goose egg-white lysozyme (GEWL, GH23)[11]. FlgJ is structurally related to a peptidoglycan degrading enzyme from the bacteriophage phi 29 [12] and also to family GH22 and GH23 lysozymes.

Catalytic Residues

The catalytic general acid is a glutamate, strictly conserved in the GH73 family. Its catalytic role has been evidenced in FlgJ [13], Auto [3], AcmA [7] and AltWN [14]. Glu185 in FlgJ and Glu122 in Auto have also been identified through structural comparison with the actives sites of GH19, GH22 and GH23 enzymes [3, 9]. However, in contrast to GH22 lysozymes, the structures of FlgJ and Auto both lack a nearby second catalytic carboxylate such as Asp52, which is the catalytic nucleophile/general base in hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL) (see figure 3). Interestingly this amino acid is present and strictly conserved in the sequences of GH73 enzymes but it is situated 13Å away from the Glu general acid in the active site.

The identification of the catalytic nucleophile/base is not conclusive. On one hand, Bublitz et al found that a mutation of the putative distant nucleophile Glu156 was accompanied of a large decrease in the catalytic activity, compatible with the role of a base activating a water molecule for the nucleophilic attack on the opposite side of the sugar ring (inverting mechanism). On the other hand, significant residual activity was found when the putative nucleophile/base residue of FlgJ , AcmA and AltWN was converted to alanine, glutamine or asparagine (for Asp1275 in AltWN), which is more compatible with a substrate-assisted catalysis involving anchimeric assistance by the acetamido group of the GlcNAc moiety. In such a mechanism a neighbouring aromatic residue is frequently involved. A Tyr residue is highly conserved in family GH73 (Fig2: Tyr220 in Auto), in close proximity to the catalytic general acid Glu. Substitution of this Tyr residue in FlgJ, AcmA and AltWN was associated with a reduced activity similar to that resulting from the mutation of the general acid Glu [7, 13, 14]. The neighboring group participation mechanism involving the general acid Glu and the Tyr as essential catalytic residues found support from the sequence comparison of family GH73 with families GH20, GH18, GH23 and GH56, which do not have a catalytic nucleophile residue [7].

Family Firsts

- First general acid/base/general acid residue identification

- First 3-D structure

- peptidoglycan hydrolase FlgJ from Sphingomonas sp. [9]

References

- Camiade E, Peltier J, Bourgeois I, Couture-Tosi E, Courtin P, Antunes A, Chapot-Chartier MP, Dupuy B, and Pons JL. (2010). Characterization of Acp, a peptidoglycan hydrolase of Clostridium perfringens with N-acetylglucosaminidase activity that is implicated in cell separation and stress-induced autolysis. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(9):2373-84. DOI:10.1128/JB.01546-09 |

- Eckert C, Lecerf M, Dubost L, Arthur M, and Mesnage S. (2006). Functional analysis of AtlA, the major N-acetylglucosaminidase of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(24):8513-9. DOI:10.1128/JB.01145-06 |

- Bublitz M, Polle L, Holland C, Heinz DW, Nimtz M, and Schubert WD. (2009). Structural basis for autoinhibition and activation of Auto, a virulence-associated peptidoglycan hydrolase of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71(6):1509-22. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06619.x |

- Rashid MH, Mori M, and Sekiguchi J. (1995). Glucosaminidase of Bacillus subtilis: cloning, regulation, primary structure and biochemical characterization. Microbiology (Reading). 1995;141 ( Pt 10):2391-404. DOI:10.1099/13500872-141-10-2391 |

- Horsburgh GJ, Atrih A, Williamson MP, and Foster SJ. (2003). LytG of Bacillus subtilis is a novel peptidoglycan hydrolase: the major active glucosaminidase. Biochemistry. 2003;42(2):257-64. DOI:10.1021/bi020498c |

- Huard C, Miranda G, Wessner F, Bolotin A, Hansen J, Foster SJ, and Chapot-Chartier MP. (2003). Characterization of AcmB, an N-acetylglucosaminidase autolysin from Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology (Reading). 2003;149(Pt 3):695-705. DOI:10.1099/mic.0.25875-0 |

- Inagaki N, Iguchi A, Yokoyama T, Yokoi KJ, Ono Y, Yamakawa A, Taketo A, and Kodaira K. (2009). Molecular properties of the glucosaminidase AcmA from Lactococcus lactis MG1363: mutational and biochemical analyses. Gene. 2009;447(2):61-71. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2009.08.004 |

- Eckert C, Magnet S, and Mesnage S. (2007). The Enterococcus hirae Mur-2 enzyme displays N-acetylglucosaminidase activity. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(4):693-6. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.033 |

- Hashimoto W, Ochiai A, Momma K, Itoh T, Mikami B, Maruyama Y, and Murata K. (2009). Crystal structure of the glycosidase family 73 peptidoglycan hydrolase FlgJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381(1):16-21. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.186 |

- van Asselt EJ, Thunnissen AM, and Dijkstra BW. (1999). High resolution crystal structures of the Escherichia coli lytic transglycosylase Slt70 and its complex with a peptidoglycan fragment. J Mol Biol. 1999;291(4):877-98. DOI:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3013 |

- Weaver LH, Grütter MG, and Matthews BW. (1995). The refined structures of goose lysozyme and its complex with a bound trisaccharide show that the "goose-type" lysozymes lack a catalytic aspartate residue. J Mol Biol. 1995;245(1):54-68. DOI:10.1016/s0022-2836(95)80038-7 |

- Xiang Y, Morais MC, Cohen DN, Bowman VD, Anderson DL, and Rossmann MG. (2008). Crystal and cryoEM structural studies of a cell wall degrading enzyme in the bacteriophage phi29 tail. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(28):9552-7. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0803787105 |

- Maruyama Y, Ochiai A, Itoh T, Mikami B, Hashimoto W, and Murata K. (2010). Mutational studies of the peptidoglycan hydrolase FlgJ of Sphingomonas sp. strain A1. J Basic Microbiol. 2010;50(4):311-7. DOI:10.1002/jobm.200900249 |

- Yokoi KJ, Sugahara K, Iguchi A, Nishitani G, Ikeda M, Shimada T, Inagaki N, Yamakawa A, Taketo A, and Kodaira K. (2008). Molecular properties of the putative autolysin Atl(WM) encoded by Staphylococcus warneri M: mutational and biochemical analyses of the amidase and glucosaminidase domains. Gene. 2008;416(1-2):66-76. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2008.03.004 |